I looked at them for a long, long time.

The plans were like big maps with black-and-white drawings of smiling, empty people. The empty people walked on tidy streets with perfect trees, in perfect clothes. The plans showed a coffee shop with laughing women sitting at a table outside. The pictures spooked me. They were drawings of ghosts trapped in a prison, only they didn’t even know it. And I thought but who would open a coffee shop in an area where there are burnt-out cars and boarded-up windows.

I’d feel sick and dizzy if I had to live in all that sameness day after day. Like the sky was falling in on you because that was the only place your eye could go, up to the blue sky, to get a rest. It took me a good three year to get used to living on the Halting Site after travelling and moving round all my life. I only moved here with my childer after my husband died in a car crash. The Site is way off the main street, in a greenfield area that used to feel like the countryside, but now we have a giant IKEA sign hangin’ over us.

For years they’ve been trying to stop us travelling as if it’s some kind of disease that needs to be cured. The Councils around the country put up bollards and fences and boulders in all our old stops along the roads. I don’t know what is it they find so terrifying about not being rooted in one spot for all of your days.

Time feels different when you travel. I feel different. I don’t have fancy words to describe it but it’s like when I were small and dreaming that I could fly along the road. You’re not just stuck in the world, fighting with it – the world is in you and with you and all around you.

They try to bribe and threaten us into houses and neighbourhoods where there are people who think we are all criminals, or animals. Out one side of their mouth the authorities promise us we have rights. Then out the other side of their mouth they say no, we never promised that at all. You have to move into houses on the other side of the city, and by the way we’re closing down the Halting Site altogether. Then they change their minds again. We are forever at the mercy of their plans. They won’t let us travel where we want, and they won’t tell us if we can stay here until our childer are grown.

Settled people pluck words out of the air like snowflakes: the words are real for a short time and then they melt away and are forgotten. They have no memory for all their clinging to the one spot.

Our men think the plan is to make our lives a misery to try and force us out that way. The Council and the ESB won’t service our site properly, and the site here almost twenty year. The power still cuts out all the time, in the middle of your favourite programme or when you’re making the dinner. And don’t talk to me about the water supply. It’s like those plans they showed us – they don’t see us as human, just as things to be moved around at their whim.

It’s not just us Travellers they treat like that. They do it to their own too. Like the time they shut off the heat in the almost empty tower block a few Christmasses gone by. That was the time we had all the snow. A woman froze to death in her own flat. She sent her kids to her mother’s but stayed to stop her stuff being stolen, and she died of the cold. They found her naked, in her bath. Stone cold dead.

God rest her soul.

Poor cratur was one of the ones left who hadn’t gotten a new house yet. Once the country went broke, the regeneration work slowed down. I heard they told her she could move to another council flat where she’d know no one and be miles away from her mother and sisters. People said they turned the heat off in the Tower to make her and the few others left move out. It’s hard to know what to believe.

The council and the Regeneration crowd and all the community services all say they are trying to help but they don’t seem to be helping anyone except themselves. They don’t live here and they get their good wages and they don’t have people looking at their lives and judging how they live.

They have all these words they throw at you like little knives – community spirit – participation – literacy skills – personal development – achievements – life skills – outcomes – outputs.

I’m not sayin’ some of it isn’t good. They set up the kids’ playgroups and homework clubs, and the learning for us women. They even built the kids a playground. It’s just they all want you to change. They’re obsessed with learning you how to change, improve, get skills. As if I’m ever going to be given a job by a settled person.

And the thing that bothers me is that they get to stay the same. You can’t look back at them and say to them what you think they should change.

Sometimes when I were struggling to learn a word, to make out the sound and meaning of it, and June, the literacy tutor, was urging me on, I got mad and thought, nothin’s right for these people. They think they have all the answers. They get the big wages, and we get people in telling us how to do this and do that, as if we’re stupid and know nothin’ at all about life. I left school at thirteen so maybe I don’t know much, but then what can you learn when the teachers sit you down the back of the class with colouring pencils and a scrap of paper for eight years.

But it turns out that I really took to the reading. I passed all my tests and started helping the others with their reading and it’s something that makes me proud. I can help my childer with their homework now. But there’s a part of me that’s also sad about it, like I’m losing something. I can read their stories and their newspapers and even though my eyesight is perfect I feel like I’m wearing a pair of glasses belonging to someone else. I’m afraid I’ll start to see the world through their eyes only.

Although their world is so strange I don’t think that’s likely. I’m thinkin’ of our disastrous field trip to the Art Gallery. The tour guide stood well away from us and used strange words we didn’t understand to describe the even stranger pictures. I mean most of them weren’t even things you could recognise.

The one good thing that I did see in the Gallery, that stayed with me, was an old black-and-white film. You sat in a little darkened room and watched the film projected onto a white wall. I was the only person who sat to watch it that day. The others went ahead with the tour guide who was rapidly losing her patience because we were talking too much and laughing when we shouldn’t.

I read the little sign by the door that said it was written by an Irish man called Samuel Beckett and that it starred Buster Keaton. I’d never heard of neither of them.

In the film, an old man goes around and around a room covering anything that might be looking at him – the window, the mirror, the goldfish in a bowl, a parrot. The camera never shows his face, just the back of him. He throws out his cat and dog. He imagined there were eyes all over the room. When he has all the eyes covered he sits in a rocking chair and looks at family photos of his mother and father and him. Then he tears them all up.

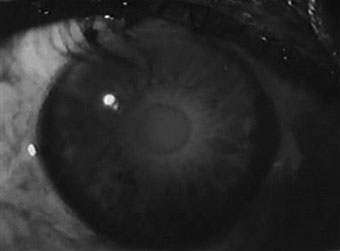

The film has no sound and I’m getting goosebumps from the silence. I don’t want to watch the film anymore but I can’t leave until I see what happens at the end. He falls asleep in the chair but he could also be dead. The camera creeps around the crumbling walls of the room and then stops in front of the man and you can finally see his face. Then he looks at the camera and you can see that he can see himself standing there looking at himself.

If the others were in the room, I would have laughed and made a joke. What a stupid film, what does it mean, it’s not about anything. But when it gets to the open staring eye at the very end I feel very, very sad. The kind of sadness that is a relief because it is a pure sadness, not mixed with anything else. The eye closes and the screen goes black, and the film starts again with an open eye.

I left the dark room and went out into the bright corridor and found the group waiting for me around the next corner. Our community worker, Grainne, had to cut the tour short and brought us to the coffee shop where the people stared at us like we were aliens. Then Winnie had one of her episodes. Winnie has what they call mental health problems, but she just suffers from her nerves. People stared at us as I talked calmly to the screaming and crying Winnie. I put my arms around her and led her slowly out of the coffee shop. I didn’t care who was looking or what they thought. I knew Winnie inside out, knew her troubles and her worries. She was just frazzled from being in a new place. She calmed down when we got outside, and we sat on the grass, and I held her hand. And then I knew what it was that I liked about the film even if I didn’t understand it. Without using words it showed some of the deep, dark fear that haunts us all. When it comes down to it, we all suffer from our nerves.

Winnie is with the Lord now. We gave her the burial she wanted which took some work I can tell you. We had to find a private spot in a bog down the country, away from prying eyes, and we set her caravan on fire. Of course she wasn’t in it – you can’t do that anymore. There’s not much you can do anymore but at least I know her spirit is at peace. I’m still here in the Halting Site but I don’t know if someday I won’t have a weakness and accept one of those houses. But I have bad dreams every now and then that I’m in a house like the one in that film and the walls are crumbling and I’m creeping around the edges of the room trying to cover the windows, the mirrors, the pictures of my family, and all the while I can feel a pair of huge eyes burning into my back.